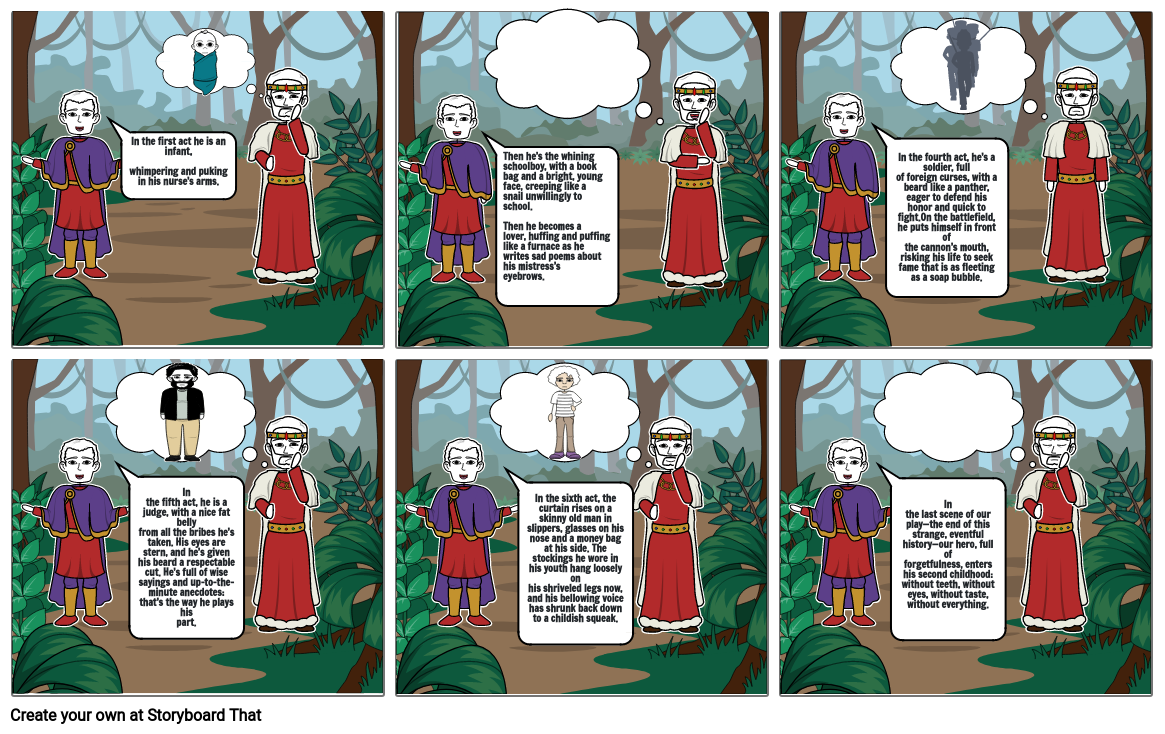

Seven stages of life

Storyboard Text

- In the first act he is an infant,whimpering and puking in his nurse’s arms.

-

- Then he’s the whining schoolboy, with a bookbag and a bright, young face, creeping like asnail unwillingly to school. Then he becomes alover, huffing and puffing like a furnace as hewrites sad poems about his mistress’seyebrows.

-

- In the fourth act, he’s a soldier, fullof foreign curses, with a beard like a panther,eager to defend his honor and quick to fight.On the battlefield, he puts himself in front ofthe cannon’s mouth, risking his life to seekfame that is as fleeting as a soap bubble.

-

-

- Inthe fifth act, he is a judge, with a nice fat bellyfrom all the bribes he’s taken. His eyes arestern, and he’s given his beard a respectablecut. He’s full of wise sayings and up-to-the-minute anecdotes: that’s the way he plays hispart.

-

- In the sixth act, the curtain rises on askinny old man in slippers, glasses on hisnose and a money bag at his side. Thestockings he wore in his youth hang loosely onhis shriveled legs now, and his bellowing voicehas shrunk back down to a childish squeak.

-

- Inthe last scene of our play—the end of thisstrange, eventful history—our hero, full offorgetfulness, enters his second childhood:without teeth, without eyes, without taste,without everything.

Peste 30 de milioane de Storyboard-uri create